FREAKS:

Re-Evaluating A Screen Classic

by Ronald V. Borst

Reprinted from Photon #23 (Published 1973)

© 1973 by Mark Frank; used by permission of the author and the publisher. The author requests that the reader keep in mind that this thesis is based on the prints available at the time of the article's publication, which did not include the now-available final sequence in Hans' estate (see Footnote 16 in the Freaks script synopsis for more on this).

|

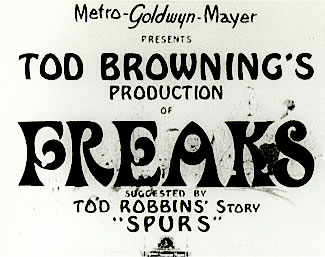

The opening title card for Freaks. This title card is suddenly torn away by the carnival barker, whose spiel about the freaks introduces the film. |

Over the period of the last forty years, one particular horror film from the early thirties has continued to garner increasing laurels and plaudits until it has eventually arrived at such a pinnacle of respect and awe that it is considered to be almost singularly immune from any form of criticism, safely enjoying a reputation of being the most startling and terrifying example of cinematic horror of all time. A film so supposedly shocking, that most contemporary critics panned it as being "too repulsive" and "nauseating," leading many exhibitors of the day to refuse to book the picture after its initial openings; so horrifying, that even subsequent reissues of the film under various other titles (i.e., THE MONSTER SHOW; FORBIDDEN LOVE; NATURE'S MISTAKES), including the original, failed to draw any greater crowds than the first release had. The film was banned in Great Britain until 1963 and, to this day, has never been televised in any country anywhere in the world. Subsequently, its absence from television coupled with the general audiences' massed reaction against it has made the film something of a hard-to-screen item until recent times, when its legendary fame as the "ultimate" in horror films led to frequent showings in metropolitan art houses and college campuses across the nation. But the years of condemnation coupled with that old film argument (i.e. that any major old horror film from the thirties is automatically regarded as a "classic") have sustained a legend . . . a legend which has never quite been justified by the film itself.

This then, is a broadly-stated, personal interpretation of the fame which has grown up over the years around Tod Browning's 1932 production of FREAKS. That there at least was a legend there is no doubt. Early issues of the professional monster magazines such as Famous Monsters of Filmland and The Castle of Frankenstein lauded the film's merits, the latter publication citing period reviews and running a half-score of graphs in their fourth number which only served to further what the appetites of these who had not yet had the opportunity of seeing the film for themselves. As with other unseen films of the time, such as THE GHOUL and MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM, the publication of choice stills, reinforced with lavish praise, served only to perpetuate the legend that the film was an unqualified masterpiece to a great many people who had only recently become interested in early horror films. Since that time the greatness of both THE GHOUL and MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM has been somewhat shattered by the rediscovery of both films, but while the weaknesses of these films have been discussed along with their laudable qualities, the deficiencies of FREAKS have all but been ignored or purposely overlooked. It is with this view in mind . . . to place FREAKS in a more proper perspective as a horror film . . . that this review is being undertaken.

Regarding the legend surrounding FREAKS, Carlos Clarens has written: "That FREAKS was made at all is extraordinary. That it was made at Metro . . . seems hard to believe." The author's statement may be a bit of hyperbole. FREAKS went into production during a time when the sincerity, creativity and quality of screen gothism was perhaps at its all-time highest peak. With the near-phenomenal success of both DRACULA and FRANKENSTEIN, is it to be wondered that all of Hollywood's major studios immediately sensed the box-office gold that lay in the making of these grim tales of escapist fantasy? Surely, there can be no denying that M-G-M was anxious to reap the profits that horror films offered to provide, and although they never geared production towards a set program of films in the macabre genre (as Universal, RKO and other studios did), M-G-M, it may be recalled, had released an impressive number of weird melodramas in the previous decade, featuring, as often as not, Lon Chaney in some new and bizarre role, with Tod Browning at the helm. The M-G-M silents, THE UNHOLY THREE (1925), THE SHOW (1927) and THE UNKNOWN (also 1927), all directed by Browning, depicted physical abnormalities within the context of a melodramatically devised screenplay when horror films were more commonly classified under the general heading of mysteries. With the arrival of the talkie era and the straight supernatural thriller replacing the standard old house cloaked killer vehicles, FREAKS emerges as a logical, if indeed, ultimate extension of these previous films, not to mention M-G-M policy.

Bob Thomas' recent biography, Thalberg—being an account of the life and times of Irving G. Thalberg, Metro's production genius of the twenties and thirties—reveals one anecdote of how FREAKS came about. "I want you to give me something even more horrible than FRANKENSTEIN," Thalberg ordered scenarist Willis Goldbeck. Goldbeck collaborated with Leon Gordon in developing a script "about bizarre happenings among freaks of a circus sideshow," based on an obscure Tod Robbins story entitled Spurs which had appeared in Munsey's Magazine some nine years before. Their original draft was then submitted to the youthful M-G-M executive who was said to have replied, "I asked for something horrifying and I got it." Thalberg went on to personally sponsor the production against massive studio opposition, eventually convincing Louis B. Mayer that the film had the potential to equal the financial success of the Universal vehicles.

Another story—this version related in Peter Haining's anthology of filmed gothic fiction, The Ghouls, and vaguely supported by text in the original studio pressbook—places the inspiration of the film with Harry Earles, the midget actor who had appeared in both film versions of Robbins' novel, The Unholy Three. According to this account, Browning had been searching for a property he could adapt to the screen in which he could prominently feature his old friend, and the actor in turn had suggested Spurs to the director, who then approached M-G-M via Thalberg.

Whichever story is true (if either; although it seems more logical to believe that Browning would have been connected with the project from the beginning if only for his prior acquaintance with Robbins ' work and former background with traveling circuses [see Footnote 1]) there is no room for argument that FREAKS owes its entire basis to Spurs and it is fascinating not only to compare the original fiction with the finished celluloid work, but to speculate what kind of film FREAKS might have come off as had it been faithfully translated to the screen. Like the film, the original story is set within a small traveling circus somewhere in the contemporary French countryside. A circus midget, Jacques Courbé, falls hopelessly in love with the troupe's bareback rider, the lovely Jeanne Marie, who accepts his proposal of marriage only when she learns that he has just inherited a huge sum of money. She and her lover, the strong man Simon Lafleur, plan to wed as soon as Jacque dies from old age, which Jeanne believes will be soon. During the wedding celebration, Jeanne becomes drunk and belittles her small bridegroom, declaring loudly that she could carry him on her shoulders from one end of France to the other. A year passes, a year in which Jeanne Marie and her "Hercules" are separated from one another, Jacques having retired from the circus and taken his wife with him to his large inherited estate. One day, Simon is startled to find a haggard and barely recognizable Jeanne Marie standing before his wagon door. The woman pleads with him to protect her from her midget husband, declaring that he has never forgotten nor forgiven her for her callous remark that she should carry him on her shoulders from one end of the [French] country[side] to the other. Each day, a virtual prisoner, she has been forced to carry Jacques from dawn till dusk down lonely stretches of rural road, after which he has accordingly marked off the miles traversed, this to be continued until the total distance has been covered. Jeanne has been unable to resist or escape because of the midget's powerful and intelligent wolf-dog, St. Eustache, who accompanies his master everywhere. As Jeanne concludes her woeful tale, Jacques enters the wagon, mounted on his canine steed, a little sword at his side. Simon attempts to prevent Jacques from retaking Jeanne, but the strong man's brute strength is of little use as the ferocious animal pins him helplessly to the floor, and Courbé silently dispatches him with his blade. Jeanne, completely humbled and resigned to her fate, places her small mate upon her shoulders and weakly trudges off in the direction of their home, Jacques' tiny "spurs" threatening to prick her if she falters in her pace. The final irony of the narrative comes when the owner of the circus notices the departure of his old friends from a long distance off. He mistakenly remarks to himself how unkind it is of Jeanne Marie to continue to henpeck her husband in such a cruel manner as carrying him around on her shoulders.

For the screen adaptation, Browning and his writers not only chose to discard the story's original title, but vastly altered the characters of Jeanne Marie, Simon and Jacque as well. (See Footnote 2) Hence, Jeanne Marie and Simon became Cleopatra and Hercules, names which perfectly suited their physical beauty and strength. Conversely, the Jacques Courbé character became Hans and, rather than being a somewhat vindictive fiend, he is a thoroughly pitiable but proud man, thereby making the contrast between goodness and evil all the more apparent and rendering: it is impossible for audiences to mentally ally themselves with Cleopatra or Hercules in the film's finale, as it was possible to do with Jeanne and Simon in the original story.

|

This publicity still of Tod Browning posing with some of the freaks clearly demonstrates the director's love and compassion for the "living monstrosities" he was working with. |

The director's intentions seem two-fold in retrospect; firstly, to film an entirely different and unique type of horror film . . . utilizing actual "monstrosities" culled from circuses and sideshows the world over. Secondly, to show audiences—many of whom were unquestionably familiar with traveling freak shows at this time—that the "things" they paid a dime to laugh or shudder at were completely normal in every respect but their bodies, and were governed by a "code" which was " . . . a law unto themselves. Offend one . . . and you offend them all!" Through the barker's spiel in the opening reel, Browning carefully sets his stage not only for the terrors that follow, but for what he apparently hoped would lead to a far greater understanding and acceptance for the select minority of people he has spent so much of his early life among. From the beginning of the film our curiosity is aroused (we do not see the "thing" which was once the beautiful Cleopatra in the enclosed pit, just the crowd's horrified reaction as the barker points her out), and our nerves set to witness the strange and unusual. Not entirely surprising, the first of the horrors released comes as the horror of revulsion. After a short introductory sequence in which Cleopatra, Hans and Frieda (Hans' midget love) are presented to us, the film cuts to a wooded glade in which a landowner and his caretaker are briskly walking towards a place where the caretaker warns there are "horrible, twisted things . . . crawling, whining, laughing!" The description is nearly as unnerving as the freaks' first appearance . . . as weird, contorted shapes dancing about in a small clearing. The audience has been prepared for this but the sequence is handled adroitly with a great amount of restraint and finesse in an effort to minimize the revulsion. Browning immediately achieves this effect through the character of the circus owner, Madame Tetrallini, a woman who easily gains our sympathy when she pleads her "children's" plight to the landlord. Any revulsion we may have felt vanishes at the sight of the freaks fleeing to their guardian in fear of the two men who have momentarily entered their world, and when the compassionate landowner understandingly permits the circus people to remain on his land . . . to play in the sunshine like normal children . . . he is graciously thanked by all the freaks. In the many brief scenes which follow this throughout the first half of the film, Browning continues to play upon our sympathies on behalf of the freaks, striving to illustrate how completely ordinary and similar their everyday lives are to our own, dwelling alternately on their moments of happiness and misery. We come not only to side with the freaks, but to accept them as our friends without reservation and after a while their appearance no longer serves to terrify or startle, since each sequence is so subtly framed with humor, rather than horror, in mind.

It is by approaching his work in such a manner that Browning commits a major error from a horror standpoint. He sacrifices a strong gothic theme and provides instead a large number of disjointed trivial scenes, many of which last no longer than a minute or two, and which have little bearing on the primary plot thread—that of Cleopatra's scheme to marry little Hans, then murder him for his money. The result is that in trying to present too much of a portrayal of circus life and its performers, the director has partially failed to sustain a mood of horror. He only initiates this atmosphere during the latter portion of the film and, even then, there are occasional cuts to unneeded comic relief.

Gregory Zatirka makes a few noteworthy points in his review, "FREAKS—A Study In Revulsion," in an old issue of Cinefantastique written around 1967, when he relates a particular trait inherent in most of Browning's films, this being that "the story in a Tod Browning film was always of secondary importance." Browning himself admitted this in an interview conducted in 1928, and it manifests itself in all of his sound horror films. His strength was in the creation of a death-like atmosphere, usually conceived and executed at a remarkably slow pace, unrelieved (or perhaps unhampered?) by a musical score. Zatirka went on, stating: "Browning's inability to keep the story value of his work up to the standards set by his atmosphere of doom and horror has always been a drawback to his sound films." Once again, unfortunately correct. The most often recalled portions of his greatest films from the thirties, such as the first reel of DRACULA; the sequences with the vampires stalking silently about cobwebbed halls in MARK OF THE VAMPIRE; or the shrunken human "dolls" scurrying about in the dead of night on their missions of vengeance in THE DEVIL-DOLL, are all examples of Browning at his best.

I personally find it somewhat peculiar that no one (to my knowledge) has ever dissected all the facets which compose the memorable highlights from FREAKS, for an examination reveals that these scenes do not singularly rely on the appearance of the freaks themselves. The horror in FREAKS is not, and should never be confused with, the horror of "revulsion," as Zatirka implies, for Browning does everything in his power to see that this feeling of initial revulsion towards the freaks is destroyed . . . does so very early in the film, and continues to harp upon their inner normality throughout while stressing the hypocritical characters of Hercules and Cleopatra. There is no rebuking that there may be a feeling of revulsion connected with FREAKS, but I find it far more related to still photographs than to the film itself. When I first saw the pinheads pictured within the pages of The Castle of Frankenstein, it had a profound impact on me. I was not frightened by the stills, but having never been exposed to this type of "monster," and assuming that they committed crimes as horrendous as their appearance, the feeling within me could only be described as revulsion, a distaste in looking at them. Of course, I was much younger at that time and somewhat naïve as well, but I continued to harbor these uncomfortable feelings, believing that when I ultimately did see the film, that I would leave the theater with a similar revulsion. You may imagine my surprise when, after having finally seen FREAKS, I left the film with a combination of disappointment and appreciation; disappointment in the film as a so-called horror "classic," but somewhat of an appreciation for its director who was able to destroy this previously held distasteful feeling. The reason that the film's effect is incomparable to the stills not only stems from Browning's sympathetic character development, but also because he never allows his camera to dwell upon the freaks' appearances for any great length of time in an effort to shock or horrify. The protracted closeups of the freaks are those in which they are portrayed as harmless and friendly beings; when at last they are provoked into evoking the code which bands them together against the outside world, the scenes are horrifying in the extreme, but so too, are they exceptionally brief.

Looking back at another of Zatirka's comments, that "The most moving scenes that make this film stand out, all belong to the freaks," one must acknowledge that the more unique sequences (such as the wedding feast) are perhaps the "most moving" ones, however, the segments of horror within the film belong as much to Browning's feeling for the macabre and thespians Henry Victor and Olga Baclanova as they do the actual freaks. Baclanova's line, "Midgets . . . are not strong!" delivered shortly after Cleopatra has learned of Hans' inheritance and the inspiration to use poison to kill him, is far more horrible in its mere implication than the continual appearance of the malformed attractions in their daily activities, whether it be the birth of the bearded lady's baby, or one of the several romantic encounters between stuttering comic Roscoe Ates and the charming Siamese twins. Another sequence which is particularly effective in terms of mood, is the one near the conclusion of the film in which the midget, dwarf and legless boy are assembled in Cleo's wagon after the artist returns from her evening performance. The ominous playing of the ocarina is terribly reminiscent of Ygor's similar melody in the much later SON OF FRANKENSTEIN, but far more chilling in evoking a mood of eminent peril, not so much because of the characters' deformities (midgets and dwarfs having been used in many films prior to FREAKS and thereby familiar to film-goers), but because of the way in which Browning has staged the scene: the trio calmly waiting for Cleo's return . . . her subsequent fear of their intentions . . . the mounting storm outside . . . all embraced by long stretches of prolonged silence.

There is also no denying that the shot of the human torso, a knife held tightly between his teeth, squirming through the mud towards the mortally wounded Hercules is a peak of filmatic terror, but again, a great deal of the scene's success lies with the staging of the sequence during the storm-filled night, and in a mob of menacing people slowly moving towards a helpless individual. The brief camera shot of the freaks coming after Cleopatra is terrifying as well, but it is the way in which they are revealed to us (for just a fraction of a second . . . in a flash of lightning) that momentarily shakes us. We have not seen any of the freaks pursuing the woman, and it is only when she pauses to turn back to confirm her safety, that we share in her disbelief, and the horror becomes all the more appalling when we realize that her pursuers are our new-found friends.

This raises an important question. Would FREAKS have been any less powerful a horror film per se if Browning had not made use of the more unfamiliar of the freaks? Surely, the film's uniqueness would have been reduced, if the director had replaced the pin-heads, armless girl, half-man/half-woman, et al with physically normal actors in makeup (resulting in an effect perhaps, not unlike the one achieved in ISLAND OF LOST SOULS), but would the sequence have been any the less frightening? Stretching the thesis even further, the film as a whole may have been improved upon, for had Browning been able to forsake his self-imposed task of building audience respect for the freaks, it would have permitted him to dwell on his atmospherics and major theme to a much greater extent, thereby accentuating the grand guignol.

What else might Browning have altered for the better? He could have aroused the shame of his viewers (and painted a more complete picture of circus life as well) had he presented the freaks performing in their actual acts along with the abundance of behind-the-scenes events. This is one phase of the performers' existence Browning tends to almost entirely ignore. Although the Dwain Esper prints may be lacking some footage (including a scene in which Hercules is depicted wrestling a lion [Actually a bull. –ed.]; only a second or so of this scene remains in the standard available prints), it is questionable that there were many other such sequences incorporated into the original version. Would not scenes of massed audiences . . . gaping . . . peering . . . hooting . . . at the freaks, have served as well in arousing the audiences' respect and understanding for the carnival people as well as illustrating all the more clearly which group actually is the more monstrous?

The film's climax—the night in which the freaks wreak their justice upon the strong man and trapeze artist, followed by the epilogue showing the horrendous hen-creature—have long been touted as supreme examples of screen horror, and are unquestionably a major reason why FREAKS has remained a cinematic legend. They are indeed highlights of the film, the torrential downpour being a Browning tour-de-force in which the only sounds are assorted groans, screams and the elements of nature. Nevertheless, for all that can be said of it, the chase sequence is far too brief. We must be content with the one glimpse of Cleo's face and the freaks in pursuit the camera affords us, although a longer series of shots, with Cleo racing . . . falling . . . struggling to make her way through the forest with various innocent shadows playing amongst the trees and undergrowth, climaxing in a similar way, would have made the sequence even more memorable. There remain, admittedly so, the couple of marvelous close-ups of the freaks propelling themselves through the mire towards the mortally wounded Hercules (there appears to be some footage missing here, for the strong man's fate is never actually explained in action or dialogue; an original plan was to have him emasculated, but as the film exists now, it is assumed that the freaks murdered him). Had Browning chosen to insert additional shots such as these, the result would have been even more satisfying.

|

A still frame of the duck girl lifted directly from the picture. |

The closing shot of Cleopatra—now something not entirely human, or so it appears—has long been a source of lengthy commentary as well. While most critics have readily agreed that the scene is utterly superb from the standpoint of sheer shock and surprise, the ridiculousness of the costume has long fallen under debasement. How could a lovely woman be turned into a feathered monstrosity? The answer is amazingly simple. . . . She wasn't! The freaks have obviously mutilated her face, cut out her tongue, and amputated her limbs, however the feathered costume is nothing other than something she has been clothed in to give her the appearance of a hen-woman. Taking this one step further (an exaggerated step, I fully realize, although there is nothing that disproves this theory), it is entirely possible to view the entire story the barker relates to his customers—from the flashback to the carnival up until the time of the freaks' revenge—as a purely fictional account dreamed up by the showman to dupe the crowd at the film's off-set. Looking at the climax in this way makes it entirely conceivable that the creature is no more than a human actress disguised to appear as horrible as the actual freaks in the sideshow, hardly a unique trick even by today's standards. One remark in the film somewhat serves to substantiate this surmise; the barker reveals in his introduction that a royal prince shot himself for love of Cleopatra, a statement which cannot possibly be rationalized when we realize that the gold-digging female would never have allowed such a life of luxury to escape her grasp, even if it meant marrying a midget! This may be an inconsequential flaw, but if it is, and we accept the film's final denouement as shown, then we must in turn reject Browning's continual plea that the freaks are normal in every respect save the physical. The question which then immediately arises is whether mentally adjusted people would resort to such a terrible revenge; or rather, would they inform the authorities and allow the law to take its due course (as one of the physically normal friends of the freaks threatens Hercules she will do if the villainous pair will not abandon their scheme of slowly poisoning Hans). Even if one does decide to accept Browning's conclusion, it is impossible to imagine most of the freaks as potential torturers or murderers, even under the most extreme of circumstances. Browning has given us too much of a detailed look into their lives to convince us otherwise. By suggesting that FREAKS may be regarded in a way other than the one intended, I realize I am leaving myself open to the same criticism leveled at these critics who have imposed an abundance of Freudian phallic symbols upon KING KONG, but while the implications regarding the Cooper-Schoedsack production seem far-fetched in an unrealistic way, accepting FREAKS as a tall tale devised by a loud-mouthed showman makes the M-G-M film more believable . . . as both THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI and DEAD OF NIGHT are made more convincing by having their horror content justified through the devices of a "madman's mind" or "recurring nightmare."

Technically, FREAKS is a primitive example of film-making, even by 1932 standards. The camera work and settings are hardly on the same level as other genre efforts of the day, notably Fox's CHANDU THE MAGICIAN, Paramount's ISLAND OF LOST SOULS, United Artists' THE BAT WHISPERS or Metro's own MASK OF FU MANCHU. The previously mentioned over-abundance of trivial sequences indicate that Browning or editor Basil Wrangell erred in allowing the first half of the film to plod along so dismally through the countless barely related scenes. On the other hand, the lack of a musical score does not detract from one's enjoyment of the film, for like Browning's other horror films, music was an unnecessary quality in sustaining the director's particular type of mood. Of the featured performers, Olga Baclanova and Henry Victor individually distinguish themselves in their roles of beauty and strength personified. Not only are they overbearing in their characterizations, but they deliciously over-act throughout their scenes, adding yet another dimension to their villainy by infusing their roles with crass and semi-moronic qualities. Witness Victor's constant booming and pride in his physique, or Baclanova's side-splitting howls of delight whenever a freak is humiliated or injured in even a minor way. Top-billed actor Wallace Ford and femme co-star Leila Hyams are also effective in much more restrained characters, their major function being to provide yet another link between the theater audience and the freaks themselves. The freaks—the superbly cast Harry and Daisy Earles excluded—are not called upon to display any abundance of thespian talents but merely to display themselves as if to silently illustrate that they are not as inhuman as they visually appear. (See Footnote 3) In minor roles, Michael Visaroff (the innkeeper in both DRACULA and MARK OF THE VAMPIRE) and Albert Conti (the Lieutenant in THE BLACK CAT) are ideally cast as caretaker and landowner respectively.

Since its release some forty years ago, FREAKS has inspired one off-shoot as well as a semi-remake, these films being 20th Century-Fox's 1961 release, HOUSE OF THE DAMNED, and the independently distributed SHE-FREAK (1967). The former was set in the traditional bizarre castle, the spooks in this case being no more than a group of displaced circus freaks comprising a Giant (Richard Eegah Kiel), Fat Woman, Legless Woman and Legless Man, who had remained on at the castle after the death of the last tenant, a former carnival showman who had befriended them and given them a home. When a young architect and his wife arrive to survey the castle for a friend's law firm which handles the estate, they are met with the expected haunted house gimmicks in an attempt to frighten them away. Dependent on dark stairways and shock appearances of the freaks to terrify, HOUSE OF THE DAMNED emerged as little more than a horror programmer. Far more intriguing was SHE-FREAK, produced by the then-king of sex and sadism horror films, David E. Friedman. As in former Friedman vehicles, BLOOD FEAST, COLOR ME BLOOD RED and TWO THOUSAND MANIACS, the screenplay was devised to exploit the horror elements to their fullest. The basic theme of a callous woman who joins a traveling freak-show, marries its owner for his money, then joins with the ferris-wheel foreman in murdering him was lifted without credit from FREAKS, as was the film's climax, in which the freaks band together to revenge themselves upon the girl, turning her into a scarred reptile-woman. Bathing in delights such as a jar containing a pickled two-headed baby, Friedman's production failed to garner the film any special critical notice coming as it did, at a time when the blood and guts horror film was a generally accepted thing. Lacking the intelligence and sincerity that went into FREAKS, it serves to prove, if nothing else, that a film like FREAKS would not be condemned by the public in our modern world, a world which has experienced far too many horrors, fictional and actual, to be disturbed over a film featuring circus freaks.

Today, the original FREAKS can only be regarded as an exceptional curiosity from the early days of the horror talkies, relying on two or three scenes to sustain its "classic" status. However, for 1932 audiences . . . the same movie-goers who shrunk back in fear at the sight of Chaney's unmasked visage in THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA, who found such primitively filmed efforts as DRACULA truly horrifying and who had yet to experience real-life monsters, such as Hitler & Eichmann, the sight of such monstrosities as displayed in FREAKS must have had far greater effect than the reaction it has on current audiences. Browning's efforts to make the unnatural attractions appear more normal obviously did not succeed with those contemporary masses; the feeling of revulsion and the unfamiliarity with horror films being too difficult to overcome for too many of them in spite of Browning's immense talents. Nowadays, these talents are far more successful in attaining their original goal, and much of what was horrible is minimized. By accepting his work as he originally intended, at least in part, with a great deal of sympathy and understanding, Browning is revealed as a director who was, in his own way, far ahead of his peers. That Irving Thalberg supported the project also says a lot for his own sophistication towards the film medium.

Footnotes:

1. One mystery concerning FREAKS, which has yet to be satisfactorily explained, is the existence of a production still, circa 1930, showing Tod Browning helping Lon Chaney into a hen costume similar to that which Olga Baclanova wore in the film's climax. The still (reproduced in Famous Monsters #22) might imply that Browning had the concept of the film in mind before Chaney's death in August of 1930. If true, this would cast grave suspicion on the ''Thalberg Story." (Return to Text)

2. The title FREAKS was not as original as it appears. Walt Lee's Reference Guide to Fantastic Films: Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror (Vol. I) reveals that Joker Films produced a silent FREAKS in 1915. The film was produced & directed by Allen Curtis, featured William Franey and Max Asher, among others, and could be termed a borderline horror film because of its use of actual circus freaks. (Return to Text)

3. Angelo Rossito, the dwarf in FREAKS, later went on to play in several other minor horror roles, usually as one of Bela Lugosi's familiars, including SPOOKS RUN WILD (1941), THE CORPSE VANISHES (1942) and SCARED TO DEATH (1947). For years a familiar sight as a Hollywood newsboy, he recently appeared with Lon Chaney and J. Carroll Naish in DRACULA VS. FRANKENSTEIN. (Return to Text)